Free recall: why it's more effective than flashcards

(5 minute read)

Free recall is a powerful study method supported by decades of research. We'll explore what it is, why it works so well, and how to actually use it.

Adapted from Karpicke, J. D., & Blunt, J. R. (2011). Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying with concept mapping. Science, 331(6018), 772–775. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199327

Why free recall works: the science behind effective studying

Free recall is simple. You just recall everything you can remember about a topic in no particular order. You can either recite verbally or write on a blank sheet of paper. Could an act so simple really be effective?

In the study above, students read a short scientific text and then studied it using different strategies: repeated reading, concept mapping, or free recall. One week later, students were tested on both their recall of information and their ability to make inferences.

The free recall group significantly outperformed the others on both measures [1]. Here are several reasons why:

Cue independence and effort

The front of a flashcard gives you a cue. It might ask, "What is the role of mitochondria?" You then remember its role as "the powerhouse of the cell" when you solve this card.

By contrast, free recall gives you no cue. For example, you try to remember everything you can about mitochondria. As you go, you might remember its role as "powerhouse of the cell."

While both methods lead to the same association ("mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell"), free recall forms this association more strongly than the flashcard. The knowledge becomes more accessible, more durable, and easier to apply to new tasks [1, 2].

It makes sense when you think about it like this:

Flashcards lead to weaker associations because the cue does much of the work for you. It's much easier to remember mitochondria's role when you see the cue on the front. You can remember it when the cue is there. But maybe not when the cue isn't there.

But when you remember something without a cue, you don't depend on a cue to remember it: the knowledge is cue-independent.

Retrieval-induced plasticity

After a free recall, your memories become moldable, like soft clay. Your memories are especially primed to be corrected. If you view feedback after performing the free recall, everything you see that doesn't match your expectation is adjusted by your brain.

Metacognition

On an exam, your task is not to "know things": you can know things and still not remember them on the exam. Instead, your task is to remember things when needed.

If you can free recall a fact, you can remember it no matter how the exam question is worded.

Free recall highlights the gaps in your knowledge. You don't actually know what you're able to access until you try it without help. For many students, this only occurs when the exam is already underway.

Now you can fix these gaps before the exam.

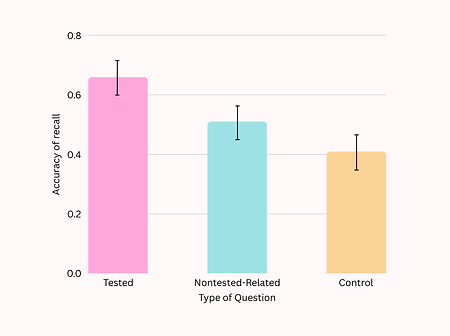

Testing Effect #1: related, unrecalled knowledge

The benefits don’t stop at the concept you’re recalling. Free recall strengthens related, non-recalled knowledge [4].

For instance, if you free recall everything you know about fruits, your knowledge of vegetables becomes stronger.

It works because free recall forces you to search your memory widely to find the answers. That search activates a lot of related information, most of which you don't even consciously think about. You can think of it like "lighting up" a region of your memory. Those “almost remembered” ideas still get stronger just from being activated.

Adapted from Chan, J. C. K., McDermott, K. B., & Roediger, H. L. III. (2006). Retrieval-induced facilitation: Initially nontested material can benefit from prior testing of related material. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 135(4), 553–571. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.135.4.553

The effect is observed after free recall (pictured above), but not after cued recall (like flashcards).

In addition to strengthening activated knowledge, your brain also has a complementary supression mechnism. If something is activated and directly competes with the answer you end up retrieving, your brain suppresses it so the correct answer can come through more clearly.

This makes the memory you retrieved stand out more sharply from nearby, similar memories.

For example, if you're trying to remember your favorite food and “cake” comes to mind, your memory for “cake” gets stronger. If “pie” also becomes active during the search because it’s similar and part of the same mental neighborhood, our brain briefly pushes it down so it doesn’t interfere. That’s why “cake” strengthens while “pie” can get slightly weaker: not because it’s in the same category, but because it became a real competitor in that moment.

In sum, this process organizes your mental schemas. The memories that get activated become better connected, while overly similar competitors get tuned down. Over time, this helps your brain build cleaner, tighter concepts and makes recall lead to better understanding.

Testing Effect #2: future knowledge

If you learn new information after a free recall, that new information is better understood and retained [5].

While flashcards lead to simple associations, free recall makes you confront your big-picture understanding. This helps organize knowledge into structured frameworks. It's easier to learn new information when you have an organized, big-picture understanding.

You can imagine how this begins a virtuous "cycle of understanding": better learning now --> better future learning --> better way future learning -> etc.

Efficiency

Through the simple act of remembering whatever, you can surface substantially more details per minute than flipping through flashcards.

Ten minutes of free recall might yield the equivalent of hundreds of flashcards, except you generate both the cue and the response, leading to robust memory traces.

Why don't most students use free recall?

Consider this strange trend: the more effective a study technique is, the less effective it is perceived to be by students [6].

Actual performance

Metacognitive predictions

Adapted from Karpicke, J. D., & Blunt, J. R. (2011). Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying with concept mapping. Science, 331(6018), 772–775. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199327

vs.

The evidence suggests that free recall is extraordinarily effective.

But it's difficult to see that in the moment: free recall really shines in the long term. In the short term, free recall is difficult, mentally taxing, and less immediately effective than re-reading [7].

It makes sense that free recall is perceived to be less effective than re-reading, which is easy and immediately rewarding.

How to make free recall even more effective

Here are some practical tips I've picked up using free recall over the years.

1. Always Recall First.

Don't start a study session with reading.

Especially if you don't know it well. Struggling to recall something you almost forgot strengthens that memory. Even more than recalling something you already know well [8, 9]. If you peek first, you lose the chance to get these major gains. No harm in trying.

Even if it's a completely new topic, trying to recall what you know already makes it easier to integrate knowledge when you study it afterward [10].

2. Writing > Verbal

I find that writing/drawing out your free recall tends to be better than reciting it verbally. Writing gives you more "jumping-off points" to recall even more information. It gives you a bit more cueing, but the cues are self-generated. Regardless, more recall is better than less.

3. Self-explanation

The less "reciting" you do, the better. Explaining in your own words forces deeper processing and highlights the gaps in your understanding .

Free recall is great for facts and concepts. But it isn't as useful in math or chemistry. It doesn't make sense to practice recalling information: the exams test problem-solving. It's better to practice for those classes by solving problems.

Studying isn't yoga...

...it’s powerlifting. Your brain adapts to deliberate, effortful practice—not 10,000 Anki cards.

Most students waste entire days “studying” without feeling prepared. SAM distills decades of cognitive science into a brutally efficient system that multiplies your results 3–4x.

I made the first part free, and it's just a 10 minute read. Read it, save hours, no strings attached. I'm sharing it because it's genuinely very useful and I want you to see for yourself.

Why SAM?

-

Add back 10–15 hours a week—the equivalent of a whole day—without falling behind.

-

Two-hour read. Lifetime return.

-

Zero guesswork. Zero wasted time. Know exactly what to do for every course, every exam, every semester.

-

Unlock med school, law school, or any grad program without burning out your time, energy, or sanity.

References:

1. Karpicke, J. D., & Blunt, J. R. (2011). Retrieval Practice Produces More Learning than Elaborative Studying with Concept Mapping. Science, 331(6018), 772-775. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199327 2. Roediger, H. L., & Butler, A. C. (2011). The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2010.09.003 3. Anderson, M. C., Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (1994). Remembering can cause forgetting: retrieval dynamics in long-term memory. Journal of experimental psychology. Learning, memory, and cognition, 20(5), 1063–1087. https://doi.org/10.1037//0278-7393.20.5.1063 4. Chan, J. C., McDermott, K. B., & Roediger, H. L., 3rd. (2006). Retrieval-induced facilitation: initially nontested material can benefit from prior testing of related material. J Exp Psychol Gen, 135(4), 553-571. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.135.4.553 5. Arnold, K. M., & McDermott, K. B. (2013). Free recall enhances subsequent learning. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 20(3), 507-513. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-012-0370-3 6. Kornell, N., & Bjork, R. A. (2008). Learning concepts and categories: Is spacing the "enemy of induction?" Psychological Science, 19(6), 585–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02127.x 7. Palmer, S., Chu, Y., & Persky, A. M. (2019). Comparison of Rewatching Class Recordings versus Retrieval Practice as Post-Lecture Learning Strategies. American journal of pharmaceutical education, 83(9), 7217. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7217 8. Butler et al. (2008) – Correcting a metacognitive error: Feedback increases retention of low-confidence correct responses. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 34(4), 918–928. 9. Karpicke & Roediger (2008) – The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science, 319(5865), 966–968. 10. van Kesteren, M. T. R., et al. (2018). Integrating educational knowledge: reactivation of prior knowledge during educational learning enhances memory integration. npj Science of Learning, 3, 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-018-0027-8