Prepare

Spend minutes now, save hours later (5 min read)

Here’s my bold claim: if you spend 5 minutes preparing before a lecture, you can save 2 hours of studying later on.

The reason lies in an extremely valuable, yet little-known concept.

How learning works in 30 seconds

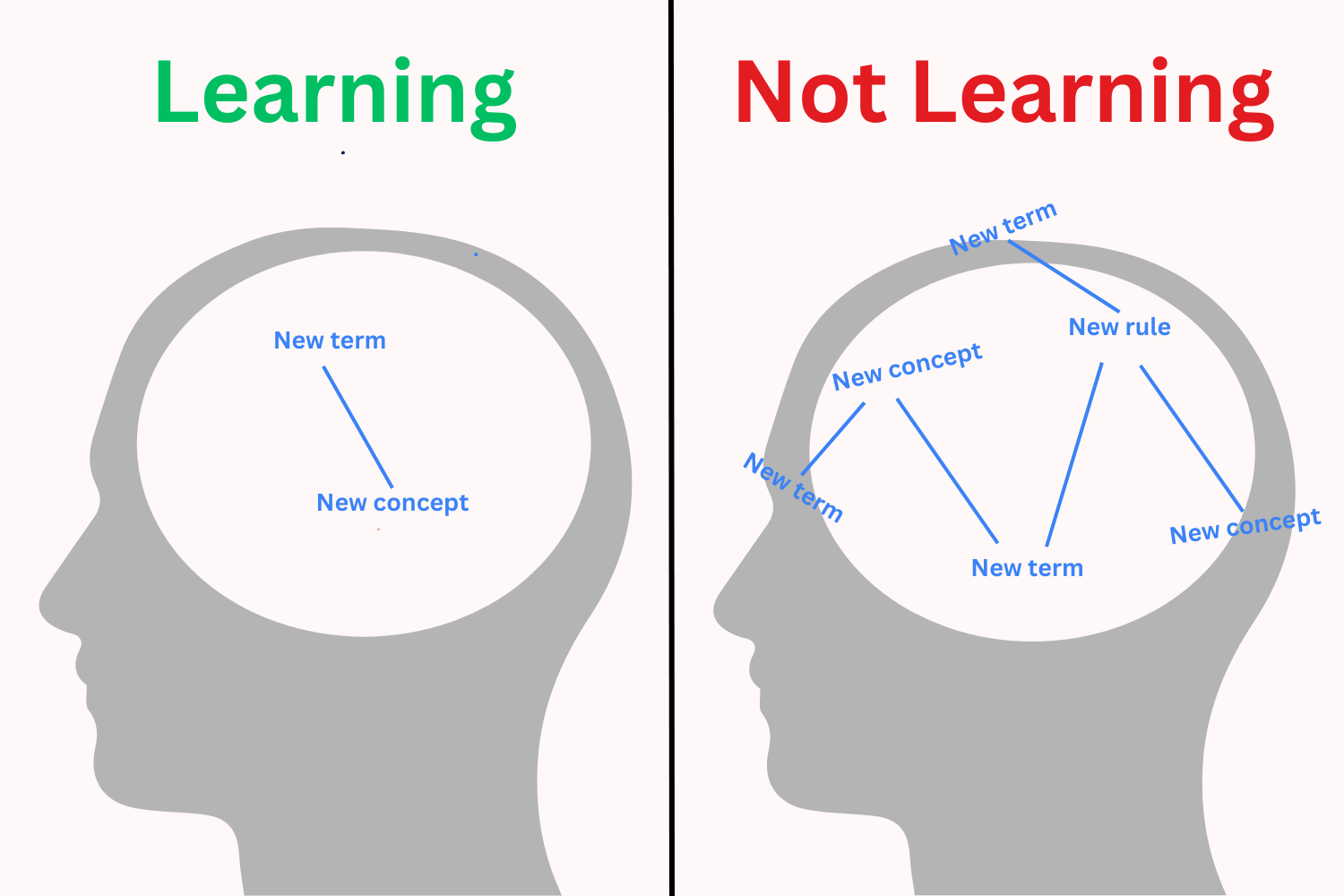

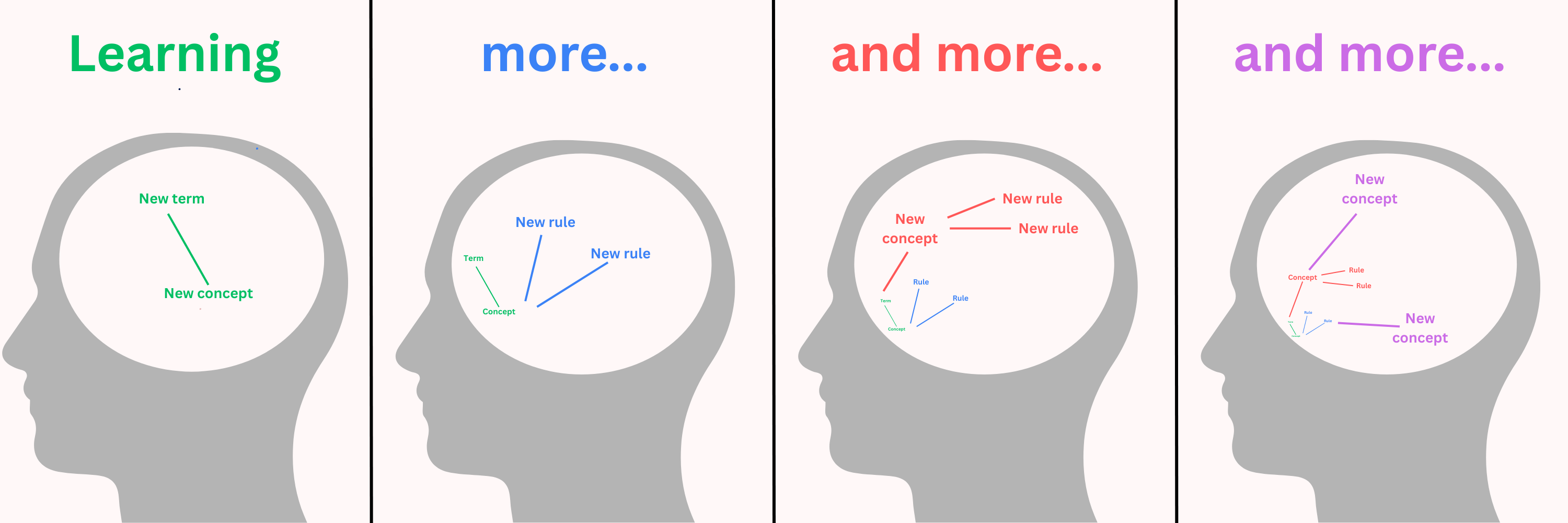

You have a mental workspace where you process information: it’s how you learn things. Your mental workspace is extremely small [1, 2]. If the new information “fits” into this mental workspace, you learn. If not, you don’t [3].

When you learn something, it takes up less space [3]. This allows you continue learning more and more.

Consequently, you learn best when you add new information slowly and gradually.

That’s great for self-study, but you can’t control lectures. Lectures tend to give you far too much information and far too little time to understand it.

If your mental workspace gets overloaded, you fall behind. When you fall behind, learning stops. When learning stops your mental workspace gets more overloaded, and you fall further behind, and so on…

Pre-training before the lecture allows you to compress some of the knowledge ahead of time. Everything presented will fit more readily into your mental workspace. You avoid the negative cycle above, and instead kickstart a positive one: your knowledge continues to grow and compound throughout the lecture.

Hence, why 5 minutes of preparation can save you 2 hours of studying later on.

Here’s a simple, science-backed way to pre-train efficiently.

How to pre-train:

Have you ever been encouraged to “figure it out” on your own in a class? Maybe you were asked to derive a theorem or make a prediction. It’s thought to help you learn deeper, but it's false: all the evidence seems to point to the contrary.

For beginners, explicit information is learned in less time, with less effort, and with fewer misconceptions. Decades of research have repeatedly confirmed this truth [4, 5].

So you have to find some explicit information and learn it. In the next two sections, I’ll quickly tell you…

-

what information to find

-

how to learn that information

…and you’ll be on your way to saving lots of time.

1. What information to find

Because we’re lean and efficient, the goal is to learn…

-

the least amount of information…

-

…that’s most relevant throughout the lecture

In other words, we want to learn foundational knowledge.

Learning foundational knowledge saves much more processing power than learning small details. Here are a couple examples to illustrate my point.

-

Before a biology lecture on cell structure, it’s helpful to know the main differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, and the names and general functions of each organelle. If you already know those things well, the rest of the lecture is much more manageable.

-

Before a history lecture on the causes of the American Revolution, it’s helpful to know a few major events leading up to it, and the major powers involved. If you already know those things well, the rest of the lecture is much more manageable.

Those are both foundational knowledge. There’s no exact science to finding foundational knowledge. You can ask an AI for an overview of the topic to be learned, or find a video introduction.

Some topics deal with facts and concepts like those above, but other topics are all about problem-solving. You’ll find a lot of problem-solving topics in algebra, calculus, physics, organic chemistry, etc.

For those topics, the best practice is to find a couple of already-solved problems to study. If you’re new to a topic, solved solutions are generally much more efficient than solving problems [3, 6].

It sounds counterintuitive at first, but it’s the same idea as described above. Trying to solve a problem without knowing what to do generally overloads your mental workspace and doesn’t lead to productive learning.

In sum: for information-heavy topics, find an overview. For problem-heavy topics, find a few problems. For topics with elements of both information and problem-solving, either is fine. As long as it clears up some mental workspace for the lecture, it’ll work.

Now that you’ve found what to learn, let’s talk about how to learn it.

2. How to learn the information

Here’s how to learn anything in two steps:

-

self-explain (while looking)

-

recall (without looking)

Step 1: self-explain (while looking)

To re-orient, you now have some information in front of you. But you don’t automatically learn just by looking at it. Passive viewing generally feels more effective than active learning, but leads to worse performance [7].

Passive viewing overloads your mental workspace—you're not learning. Active learning, on the other hand, forces your mental workspace to make connections, making the knowledge "take up less space".

There are many ways to learn actively, but self-explanation stands out as particularly robust [8]. When you explain a concept or a step in your own words, you make explicit connections between prior knowledge and new knowledge. At the same time, you confront gaps in understanding. It’s kind of like translating information into knowledge by putting it in terms of how you think.

Explain everything in your own words as you read it. As you follow along each solved example problem, justify each step in your own words. If there’s anything you can’t understand, use whatever resources you have at your disposal to simplify it. You can email a TA if you think it’s worth the hassle, but a simple AI explanation is usually good enough for our purposes.

Step 2: recall (without looking)

After you learn something, recalling it is by far the most effective way to strengthen it. Recall is extremely robust in nearly every outcome measure, domain, format, and learner [8]. It works, both directly and indirectly, in more ways than I can describe in this post.

Even the expectation of a future test increases learning measures [9], increasing the effectiveness of our previous self-explanation step.

The less help you get when you recall information, the more you learn [10]. For instance, recalling everything you know onto a blank piece of paper is generally more effective than solving a bunch of multiple-choice problems [11].

So, try to remember as much of the information you can without looking. If you gathered some practice problems, attempt to solve them on your own.

Finally, check the correct information one more time. This reinforces what you recalled correctly and even strengthens what you failed to recall [12].

And with those simple steps, you’re prepared for an upcoming lecture. You will be able to process everything as it’s presented, saving you from hours of catch-up.

Prepare: an actionable summary

Before lecture:

-

Find foundational knowledge on the topic to be learned

-

fact/concepts: a general overview

-

problem-solving: 1-2 solved practice problems

-

-

Explain the knowledge in your own words

-

Recall as much of the knowledge as you can without looking

References:

1. Cowan, N. (2001). The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24(1), 87–185. 2. Oberauer, K., Farrell, S., Jarrold, C., & Lewandowsky, S. (2016). What limits working memory capacity? Psychological Bulletin and Review 3. Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011) Cognitive Load Theory. Springer. 4. Alfieri, Brooks, Aldrich & Tenenbaum (2011) Alfieri, L., Brooks, P. J., Aldrich, N. J., & Tenenbaum, H. R. (2011). Does discovery-based instruction enhance learning? Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(1), 1–18. 5. Kirschner, Sweller & Clark (2006) Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86. 6. Renkl, A. (2014). Toward an Instructionally Oriented Theory of Example-Based Learning. Cognitive Science, 38(1), 1–37. 7. Karpicke, J. D., & Blunt, J. R. (2011). Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying with concept mapping. Science, 331(6018), 772–775. 8. Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving Students’ Learning With Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions From Cognitive and Educational Psychology: Promising Directions From Cognitive and Educational Psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4-58. 9. Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test‑enhanced learning: Taking memory tests improves long‑term retention. Psychological Science, 17(3), 249–255. 10. Hinze S. R., Wiley J. (2011). Testing the limits of testing effects using completion tests. Memory, 19, 290–304. 11. Carpenter S. K., DeLosh E. L. (2006). Impoverished cue support enhances subsequent retention: Support for the elaborative retrieval explanation of the testing effect. Memory & Cognition, 34, 268–276. 12. Mera, Y., Dianova, N. and Marin-Garcia, E. (2025) ‘The Pretesting Effect: Exploring the Impact of Feedback and Final Test Timing’, Journal of Cognition, 8(1), p. 41.