Study (work in progress)

Once you’ve made good use of a lecture or reading, the next step is just as important: what you do after learning. A lot of students jump straight into planning their day, checking their notifications, or starting the next task. But that transition period is actually one of the best times to reinforce what you just learned: by doing nothing.

Consolidation

Right after learning something, your subconscious mind continues working in the background to store and organize the new information through a process called "consolidation" (McGaugh, 2000).

If you immediately jump into another mentally demanding task, your cognitive resources are drawn away from consolidation, and the process is made less effective (Mednick 2011). Your hard-earned knowledge may as well be leaking out of your brain.

Instead, reducing cognitive input gives your brain the space it needs to "absorb" what you just learned. Research shows that even short periods of quiet rest without distraction after learning help improve subsequent memory and understanding (Dewar et al., 2012; Craig et al., 2015).

In short, do your best to stay distraction-free for 10-15 minutes following a lecture or reading. Breaks after learning save you time in the long run by enhancing consolidation.

Delay

Contrary to usual expectations, sooner retrieval isn't always better, even though it tends to be more accurate. Spacing out retrieval to allow some forgetting makes it more effortful, leading to greater storage strength of memory traces (Cepeda et al., 2006; Rawson & Dunlosky, 2011). This works out nicely, since the consolidation break after learning contributes to the delay.

But spacing is a double-edged sword. Memory traces tend to remain plastic for only a few hours after learning (Dudai, 2004), so retrieving within this window tends to be more impactful.

Another consideration is that waiting longer also makes it more likely that you'll completely forget some details and be unable to recall them at all. Earlier, I mentioned that failing to retrieve parts of a memory can actually weaken those parts through retrieval-induced forgetting (RIF). In other words, if you wait too long and can’t recall some elements, you're even more likely to forget them again. Retrieval must actually succeed to enhance learning (Karpicke & Roediger, 2008). If your schedule doesn’t allow for review until hours after the lecture, that's completely fine.

I lean toward the shorter end of the delay spectrum. Having an accurate schema is more important than squeezing out immediate gains in storage strength. Everything you learned has not yet been retrieved and is thus extremely prone to forgetting. You can always build storage strength with later retrieval sessions, but if you miss key ideas and have to re-learn them from scratch, it’s a far bigger hit to your time efficiency.

Aim for a review window of 15 minutes to 1 hour post-learning. But don’t stress if you miss it—just make sure you revisit the material before the day is over. That way, you can leverage the consolidation power of that night's sleep to further strengthen the memory traces (Diekelmann & Born, 2010).

Retrieval practice

After all that, we've come to my favorite part: retrieval practice. But first, I want to discuss strategy.

Bloom's taxonomy: putting it to bed

The purpose of retrieval practice is to practice doing the action relevant to your upcoming exams. That might look like recalling systems of the human body or practicing physics problems. According to a popular abstraction called Bloom's taxonomy, these two actions would represent different "orders" of learning.

In the example above, recalling biological systems would fall under "remember", possibly overlapping with "understand": the two lowest orders of learning. Solving physics problems would fall under "apply": a higher order of learning than the other action. A common interpretation is that higher orders of learning are "better," and one should always strive to create, evaluate, etc.

The most efficient kind of learning is the one that matches the expectations of the exams, even if Bloom's taxonomy considers it a lower-order learning.

For instance, free recall (reciting everything you remember) is one of my favorite techniques, but it doesn't require much beyond the first two orders of Bloom's (memory and understanding). Yet it would prepare you to ace an anatomy exam much more efficiently and more practically than trying to:

-

Evaluate (2nd top order of blooms): that might look like comparing two clinical diagnoses (e.g., cubital tunnel vs. carpal tunnel syndrome) and evaluating which one better explains the symptoms.

-

Create (top order of blooms): that might look like proposing an innovative approach to minimize nerve damage during a certain surgery, based on your understanding of anatomy.

I still believe that higher orders are valuable depending on your goals. Of course, SAM was built to pass exams in less time, but the way I see it, there's always a tradeoff. Sometimes you do really want to learn a detail really deeply, so you might go ahead and create that innovative approach in the example above, but that might be leaving 20 other similar details on the table: details you could have learned in all that time the exercise took you.

Another thing to address: this rule applies even in courses with higher-order learning. A common practice in such courses, like physics and calculus, is to "scaffold" through the orders of learning: memorize facts so that they can be more easily understood and then applied. For instance, you might practice for organic chemistry by solving flashcards or otherwise recalling factual information about the different types of reactions (SN1, SN2, E2, E1) and their conditions. But research findings give a clear consensus: skipping straight to the higher-level practice practically always leads to better learning outcomes (Agarwal, 2019; Jensen, 2014). So, you'll want to skip straight to solving the problems, even if you don't understand them. If there are any gaps in knowledge or understanding, they can be addressed when checking your answers to these problems.

It's hard to know exactly what your exam expectations will be toward the beginning of the semester. It's just a by-product of the air of mystery some professors prefer to keep, for whatever reason. This fact doesn't lend itself quite so nicely to our goals, so I use an abstraction that keeps things simple: “declarative” (knowing-type) vs “procedural” (solving-type) classes. 99.9% of courses tend to fall into one of these two categories, and it's usually pretty easy to guess which one your course falls into (biology, art history, and psychology = declarative; calculus, physics, and computer science = procedural) . Sometimes it's a bit of a mix. In these cases, you can treat the declarative and procedural knowledge independently and process them separately according to the steps below.

Declarative

For any declarative knowledge you've learned during the prior learning event, follow this process:

At this point, you already know almost everything you learned. If you don't believe it, check the source material: you’ll recognize nearly all of it as you read. The problem isn’t knowing, it’s recall. It's difficult to retrieve without the material in front of you. The memories exist, but they still rely on cues.

Our goal now is to reduce that cue dependence and thereby make the knowledge more intrinsic and self-sustaining. Once the cues you need are equal to or less explicit than the ones provided by the exam questions, you’re ready.

You get better at whatever you practice. If you practice recalling with lots of cues, like on flashcards, you only get good at recalling when those cues are there. But if the exam gives you different or fewer cues, you struggle. Free recall practices recall with fewer or no cues, which trains your brain to rely less on prompts and makes your knowledge more intrinsic and automatic. Free recall leads to far better long-term retention and flexibility than flashcards (Karpicke & Roediger, 2008; McDaniel & Masson, 1985).

And free recall is exactly what we'll do for any declarative knowledge. Simply write down everything you can remember about the topic in no particular order: no cue. Beyond the information itself, you'll be able to naturally draw relationships and associations as you go. There are too many benefits to describe within this module, and some of them are very surprising. But the key takeaway is that the lack of specific cueing makes retrieval more effortful and amplifies its effectiveness (Karpicke, 2012).

After performing a free recall, you'll want to check your understanding against a reliable source—ideally, the original material. This helps you spot any gaps or misunderstandings that may have slipped past you during class. Avoid using secondary sources like your own notes if there is a better alternative; they may reflect errors, omissions, or incomplete interpretations of the original lecture or reading.

But just reading and understanding these missed details isn't enough. There is no guarantee that you'll remember them during the next free recall. We need a way to reintegrate these missed details back into the larger schema. And there's no better way than The Mastery Loop. Read about how to do it here.

The Mastery Loop deliberately crams recall and review very close together, which means it sacrifices some storage strength (long-term durability of memory) in exchange for retrieval strength (immediate accuracy and fluency). This tradeoff is intentional: in the initial review, the priority isn’t making the memory last forever but ensuring that you can accurately and completely recall the material right away, eliminating gaps and false confidence. Future recalls will prioritize immediate return on time rather than full accuracy. But spending this extra time to ensure full accuracy in the beginning will pay dividends in time saved in the long run.

By front-loading retrieval strength, you build a solid, accurate foundation before layering on more challenging and time-spaced reviews. Once you’ve reached a level of recall you’re satisfied with, the system will progressively add desirable difficulties like spacing and cue reduction, which strengthen long-term retention without risking early inaccuracies. In other words, the The Mastery Loop makes sure you know it first, then the rest of SAM will help you keep it for as long as you need, strengthening it further along the way. More on that later.

Procedural

Here, we'll do the equivalent of a free recall but for skills rather than information: effortful retrieval for procedural knowledge. Simply attempt to perform the skill required (usually solving a problem) without any external help. Then check your answer against a worked example (which AI can also provide). If you did anything wrong, think about why, put the worked example away, and attempt to do the problem again from memory.

It may sound tempting to continue trying to solve problems without any help. After all, unguided problem-solving reflects the effortful retrieval I've been emphasizing throughout this guide, but research has shown that it actually reinforces incorrect procedures and conceptions (VanLehn, 1999). Besides, continual struggle can be a waste of time and effort, often called "floundering" in jargon.

Struggle is productive when it's followed by well-structured feedback (Kapur, 2008, 2012). Particularly, worked examples are one of the most well-established ways to get feedback, consistently outperforming unguided problem-solving, so much so that it's been coined "the worked example effect" (Renkl, 2005). Worked-out examples tell you what to do step-by-step, so your limited working memory can be spent understanding rather than simultaneously trying to solve and understand at the same time (Sweller, 1988). So try it once, really compare your understanding against a worked example, and then try it again until you get it right.

Recall that procedural practice is far more effective when you talk yourself through the reasoning step-by-step — especially the conceptual "why" behind each move. This plain-language reasoning:

-

makes underlying principles more salient and helps you notice mismatches between your conceptual understanding and the mechanical steps you're using to solve the problem (Schwartz & Martin, 2004).

-

Enhances processing by engaging more cognitive resources (Renkl, 1997, 2002) through mechanisms like dual coding (Paivio, 1991).

One last thing to be cautious of: don't move on until you do the problem correctly on your own. This ensures you’re reinforcing correct procedures—not practicing mistakes (VanLehn, 1999).

Repeat the above process for a sample of problems until it becomes automatic. The problems can be from the lecture, textbook, or AI-generated as long as they seem representative of what you're expected to do on an exam. Some professors make it hard to find a representative sample of problems. But do your best—something is better than nothing. Procedural skills are best reinforced through repetition. Repetition of similar problem-solving procedures allows learners to become fluent in the rules, enabling quick automaticity (Anderson et al., 1997). It may feel redundant, but every time you do a specific type of problem, your neural pathways associated with the solution become reinforced, and the process becomes more automatic. And don't get discouraged, because it will become automatic, even if not during the study session. Procedural skills are subject to considerable performance gains from sleep (Wagner et al., 2004).

Spacing

To recap: your knowledge has been well-encoded and reinforced through strategic retrieval. You’re in a strong position, but memory is dynamic. Without continued retrieval, you'll forget. That’s why it's critical to schedule future retrieval sessions. But you don't have to settle for just "keeping your memories afloat." By spacing them out strategically, you don’t just preserve the memory—you actually strengthen it: each successful retrieval after a delay makes memory more durable and easier to access in the future, thanks to the spacing effect (Cepeda et al., 2006). It saves you a boatload of time in the long run.

According to Ebbinghaus's forgetting curve, memory retention declines rapidly after initial learning, especially within the first few hours or days (Ebbinghaus, 1913). However, with each review, the rate of forgetting slows, meaning you retain information longer each time. And the most effective long-term gains occur when you retrieve the information just before you're about to forget it.

In short, we must schedule our future recall such that it occurs when the information is nearly forgotten. A tricky feat considering that this span of time is dynamic.

Fortunately, this kind of expanding review schedule is easy to implement using free tools like Anki. You may know Anki as a simple flashcard app—but we won’t be using it just for basic flashcards. We're more interested in what's under the hood: a sophisticated Leitner spacing algorithm.

This algorithm aims to automatically schedule your reviews at optimal intervals: when the memory is almost gone, but not completely. This is exactly when retrieval is most effective for long-term retention. These intervals are further optimized through user input. If you struggle with a card, you will see it sooner and more often. If a card is easy for you, you'll see it later and less often.

This leads to some unique advantages:

-

Maximized forgetting before reviewing the card = maximized gains to memory strength = less overall time needed to review in the future

-

Less time wasted reviewing things you already know well, more time on things that need it

-

Closed system: cards always come back before complete forgetting = no time wasted re-learning

-

Allows for seamless interleaving, an extremely powerful effect that we'll explore in a bit

Ultimately, these all compound together into tons of time saved,

Beyond that, it gives you peace of mind knowing that there's nothing you're forgetting to study. You don't have to juggle several things at once when your reviews are scheduled automatically.

Anki's spacing system is powerful. Now, imagine if the basic flashcards were replaced with effortful retrieval practice like free recall for declarative classes, and practice problems for procedural classes. That's what we'll do next. But first you'll have to bear through some setup. I'll walk you through it as clearly as I can. It looks daunting to begin with, but I promise you'll get the hang of it quickly!

Anki Setup

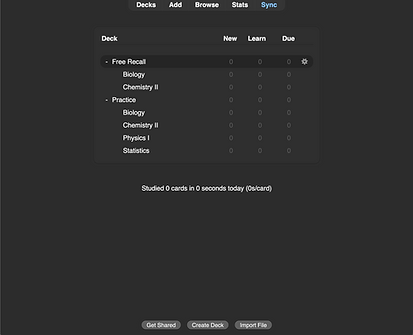

The first step is to download Anki here. It's free on Mac, Windows, and Android. Once opened, you'll be met with a screen similar to this one

The setup from this point on is minimal; we'll just create two deck templates, adjust their settings, and then we can re-use those templates for all of our classes until the end of time. One deck type will contain cards that prompt free recall, and another deck type will contain cards that prompt practice problems.

Why two decks? Free recall suits declarative knowledge (facts, concepts), and practice problems suit procedural skills (math, problem-solving). This clear split keeps studying efficient.

To create the decks:

1. Click the “Create Deck” button at the bottom center of the Anki screen. and name the first deck "Free Recall"

2. Click the same "Create Deck" button once more and name the second deck "Practice"

Now we need to go in and adjust the settings of each one. I've tested this system for years, and only a handful of tweaks are truly necessary. Starting with "Free Recall":

3. Hover over "Free Recall", and a cog icon will appear on the right. Click the cog and then click "options."

4. Change the following settings:

-

New Cards: 9999 (under "preset" tab) — uncaps daily new card limit (not usually needed)

-

Maximum Reviews: 9999 (under "preset" tab) — uncaps daily review limit

-

Learning Steps: "2h 3d" — new cards repeat in 2 hours if wrong, 3 days if correct

-

Relearning Steps: "1d" — card appears the next day if you get it wrong in the future

-

New Card Gather Order: Random — mixes cards to reduce cue-order effects

-

New Card Sort Order: Order gathered — keeps consistent order once gathered

-

New/Review Order: Show new cards before reviews — prioritizes new info to reduce forgetting

-

Review Sort Order: Relative overdueness — review least overdue first to improve retention

-

FSRS: On — advanced spacing algorithm optimizing retention and efficiency

-

desired retention: .90 — this is the "probability of success" that FSRS optimizes around. Higher = you'll know it better, but diminishing returns set in quickly. .90 is a safe choice for exam critical material.

-

Don't exit out, or it won't save. We must save the settings as a preset.

5. Click the arrow next to the blue "Save" button (usually top-right of the window)

6. Click "Rename Preset, call it "Free Recall".

7. Click the blue "Save" button

Now that your "Free Recall" preset is saved, let's finish up by making the "Practice" preset. The steps are similar:

8. Hover over "Practice" and a cog icon will appear on the right. Click the cog and then click "options"

9. Click the arrow next to the blue Save button, and then "Add Preset"

10. Name the new preset "Practice"

11. Change the following settings:

-

New Cards: 9999 (under "preset" tab) — uncaps daily new card limit (not usually needed)

-

Maximum Reviews: 9999 (under "preset" tab) — uncaps daily review limit

-

Learning Steps: "10m 2h" — shorter intervals due to faster forgetting of practice problems (because cues make forgetting happen faster)

-

New Card Gather Order: Random — ensures interleaving within practice deck, which is proven to increase learning outcomes (Hattie & Donoghue, 2016)

-

New Card Sort Order: Order gathered — keeps consistent order once gathered

-

New/Review Order: Show new cards before reviews — prioritizes new info to reduce forgetting

-

Review Sort Order: Relative overdueness — review least overdue first to improve retention

-

FSRS: On — same benefits as above.

-

desired retention: .90 — same reason as above: this is a safe level for exam-critical material.

-

Remember not to exit out, or it won't save. Let's save the settings as a preset.

12. Click the blue "Save" button

I appreciate you bearing with the setup so far. I wouldn't have you doing all this if I didn't know as a fact that you would be getting massive returns on your time investment.

Now we'll add our classes. If you're not taking any classes at the moment, way to be proactive! You have access to SAM for life, so you can come back to this part when you do have classes. But feel free to follow along for practice.

We must make a sub-deck for every class. That way, we can prevent the intermixing of practice among subjects.

To clarify, mixing within a subject is called interleaving, and it's extremely beneficial since it helps your brain distinguish concepts better. But mixing different subjects is harmful. It's called task switching (Monsell, 2003), and it leaves a "working memory trace", fragmenting your attention and stifling learning. This is easy to control if we keep our classes segmented.

To make a subdeck, simply create a new deck and drag it into an existing deck.

Now we'll make subdecks for the rest of our classes. For SAM, you'll need a free recall subdeck only for classes that require declarative knowledge (remember, these are the ones that require conscious recall of information, like biology or history), and a "Practice" subdeck only for classes that require problem solving or other higher-level performance.

-

For every procedural class, create a Practice subdeck.

-

For classes with declarative content (like biology, history), also create a Free Recall subdeck.

It's perfectly fine if you don't know which classes require declarative knowledge. Oftentimes, it's not obvious. Especially toward the beginning of the semester. Feel free to do whatever gives you peace of mind: you can always add or delete them later as needed.

All that's left to do is save the settings of the main decks to the subdecks.

1. Navigate back to the settings in the main "Free recall" deck (click the cog, then "options").

2. Click the arrow next to the blue save button at the top right

3. Click "Save to All Subdecks"

Now simply repeat this process, but for the "Practice" deck instead of the "Free Recall" deck.

Congratulations, you've finished all the setup. Next, we'll get into exactly how you'll be using it within your study system.

Scheduling Review

To reorient ourselves once more, we've finished our learning event, taken a break, and done some retrieval practice. The very next step is to schedule future reviews. Now that we've set Anki up, we can do just that.

Declarative

For declarative knowledge, we run into a dilemma: see if you can figure it out. Don't worry, there's a solution at the end.

At any given point in your studies, you have a set of memories of vastly varying strength. Many are very strong, many are very weak, and most are in the middle. Think of your memories like weightlifters in a gym. Strong memories lift heavy weights easily; weak memories struggle. Your job is to train all muscles maximally.

Similarly, you want all these memories to become stronger so you can do well on exams. They get stronger through retrieval.

The more effortful the retrieval, the stronger the memory becomes.

But here’s the catch: make retrieval too hard, and you risk failure. When the difficulty overwhelms your ability to recall, the benefits disappear. Not all of your memories can keep up. The strong get stronger, and the weak cannot participate.

Free recall is the most difficult, which is why it's the most effective. Your memories gain a lot of strength as a result, but ONLY if they can lift 100 pounds in the first place. You’ll want to strengthen the weaker memories, too. How?

Here's the solution: I call it Stepwise recall: You start with free recall and progressively give yourself more hints.

-

Heavy Lift = Free Recall:

Most difficult; targets the strongest details (the ones you can recall without a cue) -

Medium Lift = Semi-Cued Recall:

A hint reduces effort; targets moderately weak details (the ones that you can now recall with this small hint) -

Light Lift = Highly Cued Recall:

Big hint: targets the weakest details (the ones that you can only recall now that you've gotten a big hint)

It is crucial to start with free recall, because if you started by giving yourself a big cue, it would spoil the details that you could have recalled with less cueing. The stepwise approach ensures that each "trainee" (memory) is challenged at the highest level they can handle, maximizing overall strength gains across the entire group.

Stepwise recall gives memories upward mobility. If you give yourself a chance to recall a weaker memory with a hint, the memory will gain strength, and you might not need a hint next time. If you did free recall without the stepwise strategy, the weakest memories wouldn't be stimulated; they would, in fact, get weaker through retrieval-induced forgetting (Storm 2012).

Stepwise recall is a great way to squeeze all the gains possible from declarative retrieval.

It's simple to put it into practice. We'll just make a flashcard with the free recall prompt on the front. On the back, we'll put some hints and a link to the source material. We'll walk through an example to show you what I mean:

Suppose we want to make a card after a biology lecture. The topic was photosynthesis, so on the front of the card will be "Photosynthesis". It doesn't really give anything away, so it serves as a perfect cue for our free recall.

Follow along for practice:

1. Click on the desired deck (it doesn't have to be "Biology"; we're just practicing)

2. Click "add" to make a card within this deck

3. On the front of the card, type the lecture topic, in this case: "Photosynthesis"

Suppose the professor discussed a few subtopics, including chloroplasts, light-dependent reactions, and the Calvin cycle.

4. On the back of the card, type: "chloroplasts, light-dependent reactions, Calvin cycle".

Remember, these cues give away a little bit, but still give you a chance to effortfully recall something you might have missed. In this case, you can redeem yourself if you forgot all about the Calvin cycle during the free recall.

I also like to link the source material on the back of the card for convenience.

It's a good time saver to create the card while you're checking your answers from the initial free recall, so you don't have to go through the source material a second time.

After that, take a moment to recall anything you missed one more time. It may feel like overkill, but early on, your memory is especially fragile. Prioritizing accuracy over speed in these first stages prevents mistakes from sticking. In the long run, this extra step actually saves time by making sure you don’t accidentally lock in the wrong information.

5. Make sure to click "Add" at the bottom left (or shortcut: Cmd+Enter on Mac)

There are two more steps to our stepwise retrieval beyond the free recall and the semi-cued recall, and we'll get into that in the next module.

Great job! You've set yourself up for far more gains in future review.

You can delete this card since it's just for an example. Click "Browse", find the card, and right click on it, hover over "notes", and click the "delete" option that appears.

I often get this question: if recalling broader topics is better, why not just free recall everything at once—combine all the lectures and readings into one big card?

Different lectures/readings are learned at different times, which means they're also forgotten at different rates. Grouping them all makes it hard to review each topic when it actually needs reinforcement. By scheduling one free recall per learning event, each chunk gets reviewed when it’s most effective: just before you forget it.

Procedural

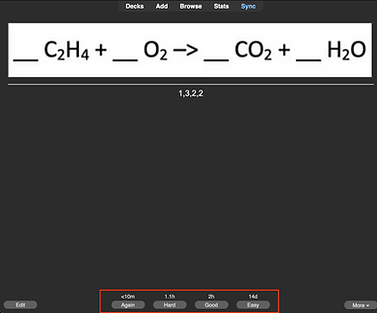

For procedural knowledge, our task is much simpler. Anki does all the legwork by spacing and interleaving automatically. We just put a representative set of problems into Anki. I find this easiest to do while I'm already doing the problems after class.

I mentioned it briefly before, but interleaving is the intermixing of problems/topics that are easily confusable (Rohrer, 2012). It's a seemingly small tweak, but it leads to massive gains in retention, particularly for procedural knowledge. All for no extra time. If you like, you can read more about interleaving here.

Interleaving isn't the default in Anki, but our deck settings ensure it always happens automatically. And it's far more effective than manual interleaving—since you don’t know what topic a question comes from, you’re forced to figure it out on your own. That’s the kind of mental work exams actually demand.

To add a practice problem:

1. Click on the subdeck under the "Practice deck" we want to add practice problems to

2. Click "Add" to make a card within this deck

3. Put the question on the front and the solution on the back. If I'm getting the questions from online, I find it convenient to copy the screenshots to the clipboard and paste them into the card (Hold Ctrl while taking a screenshot on Mac, and Cmd + V will paste the screenshot onto the card.

4. Click "Add" (or Cmd+Enter on Mac)

And that's all for post-learning! That was a lot of explanation, but once you get the hang of it, you'll knock it out in 15-30 minutes every time.

Regular Study

You've done the hard work already.

By following all the previous steps, you're set up for long-term success. Your reviews are now spaced, effortful, and automatic. From here on out, the job is simple: just keep showing up, finish all the scheduled cards daily.

Let's drive it home by walking through exactly how to review your cards:

Let’s start with your "Practice" decks, since they’re the most straightforward.

Procedural

Make sure you're following all the same procedural problem solving principles as before.

-

Try the problem on your own first.

-

Use conceptual self-explanation to talk through why each step works (Chi et al., 1989; Renkl, 1997).

-

If you get it wrong, review a worked example (Sweller, 1988), then try again from scratch.

-

Only move on once you’ve gotten it right on your own.

To review the cards, simply click the deck you want to study and then "study now".

Anki allows you to self-report how well you solved the problem. After you flip over each card (spacebar), you can click the buttons at the bottom or use keyboard shortcuts (1, 2, 3, and 4) to do so.

The settings we made for the practice already emphasize repetition, so you might see the same cards multiple times in a study session, especially if you struggled with them.

Free Recall decks require a bit more structure—here’s where Stepwise Recall shines:

Declarative

1. Free Recall:

Read the topic on the front of the card and write or say everything you can remember. No reading the cues yet.

2. Semi-Cued Recall:

Flip the card to reveal hints. Try to recall anything you missed the first time using these partial cues.

Each step builds memory strength appropriate to your current ability level—without giving answers away too early (Karpicke, 2012).

From this point on, there are actually two more levels of stepwise recall we can benefit from. As I mentioned previously, reading after a free recall feels smooth; most of what you read will mentally "click".

3. Highly-cued Recall

But something else will happen too; you'll be reminded of details you forgot as you go through the source material and check your understanding.

Here's the protocol: immediately close your eyes / scroll away and recall those details. Even if you spoiled them a bit by looking ahead, more recall is always better. By recalling before reading, you're preserving more gains from the spacing effect.

There's one final case to consider. Sometimes, there are details that you can't recall with any amount of cueing: either you recall them wrong, fully forget them, or simply don't understand them to begin with. If you've kept up with your scheduled cards, this is unlikely to happen at all. But for the sake of completeness, I'll tell you what to do.

4. Re-Recall

These tricky details require special attention. They are weak to begin with, and the fact that we couldn't recall them means they didn't gain any storage strength. Not only that, but they are likely to become even weaker through retrieval-induced forgetting (the phenomenon in which recall of information weakens related, non-recalled information).

Here's how to deal with these details:

-

Understand. Easier said than done, but it's a necessary first step. Here are my go-tos: ask an AI model to explain it to you simply. If that doesn't work, just continue asking for clarification until it gives you something. If you're persistent, this will work in 99% of cases. Rarely, you have a topic that cannot be understood with help from an AI. The only option left at this point is to keep a running list of these details and ask your professor or a TA.

-

Immediate Recall. Recalling them right after learning is not optimal, but the small strength gain will be enough to remember them next time. Just close your materials and re-explain the concept simply using The Pocket Professor, which is self-explanation in your own words, answering "What?", "Why?" and drawing as you go.

-

Schedule. Turn the detail into a highly-cued flashcard (what you would think of as a "traditional" flashcard) in the "Practice" deck. Simple memorization will not get you far, which is why I don't recommend highly-cued flashcards as a study method on their own. But Anki flashcards are perfect to scaffold weak details until they can be recalled effortfully (through free recall).

Grading the card

From my experience, when grading free recall cards, it's almost always best to choose the button labeled "good" at the bottom of the screen. It pushes the cards back at an increasing interval every time you press it. The rationale is that you can get away with it because you're effectively re-integrating everything you missed through all the above "fallback steps": stepwise cueing, the re-encoding, and the separate practice cards. Nothing slips through the cracks because of all those fallbacks. So the assumption is that the next time you see the card, you will have done the "equivalent" of recalling everything well, even if you didn't actually do it the first time.

The only case where you might select the "again" button is if the recall was so poor that it would be easier to just re-learn and try the recall again than to make any practice cards. In that sense, you're choosing "good" or "again" based on whichever is easier: doing the practice cards or just re-learning and trying again.

Breaks

As a final tip: taking low-stimulus breaks both decreases cognitive fatigue and promotes effective memory consolidation (Dewar et al., 2012). Continuing to learn without a rest period interferes with consolidation, and the new information you're learning actually inhibits the old information, preventing it from being stored effectively.

A 15-minute break every 90 minutes should be sufficient. You accomplish this with a Pomodoro-type timer if you like.

Study: Efficiency Amplifiers

A) Immediately After Learning (Consolidation)

-

Quiet, low-stimulus rest (10–15 min)

B) First Retrieval Timing (Delay)

-

Short delay before first recall (≈15–60 min)

-

Same-day revisit (before sleep) to leverage sleep consolidation

C) Declarative Retrieval Workflow

-

Free recall (uncued) as the base pass

-

Stepwise cueing (semi-cued → highly-cued) to rescue weaker traces

-

Re-recall for failed details (targeted rescue to counter RIF)

-

Source check + “Pocket Professor” self-explanation (what/why) with drawing

-

Mastery Loop (tight recall-review loop to eliminate gaps early)

D) Procedural Practice Workflow

-

Unguided first attempt (effortful retrieval for skills)

-

Worked example feedback (worked-example effect)

-

Immediate retry from memory (no peeking)

-

Conceptual self-explanation while solving (step-by-step “why”)

-

Don’t move on until correct (prevent practicing errors)

-

Short, focused repetition to fluency/automaticity

E) Spacing & Automation (Anki Setup & Scheduling)

-

Spacing algorithm (FSRS/Leitner; near-forgetting scheduling)

-

Interleaving within practice deck (automatic mixing of confusable types)

-

Deck separation by subject (prevents task switching costs)

-

New-before-review + random gather (reduce cue-order effects)

-

Cognitive offloading & “closed system” (automatic queue; no decision fatigue)

-

Card design for declarative stepwise recall (front cue + back hints + source link; logistical time saved only)

F) Ongoing Review Hygiene

-

Micro-breaks during study (≈15 min every 90 min)

-

Grading policy for throughput (“Good” default due to built-in fallbacks)

You're done!

And there you have it: that's SAM. The goal was to make this guide concise, yet packed with goodness. Structured, yet flexible enough to accommodate all coursework.

And here's the summary sheet for studying so you can reference everything easily. Feel free to save it to your bookmark bar.

Good luck with the rest of your life.

Happy studying.

-Sam

Contact me

If you have any questions at all, I'm an open book. And any advice you have to improve the system is greatly appreciated.

My goal is to make SAM work for every college course. If the system doesn't seem to work for one of yours, shoot me an email and we'll fix it.

References:

Agarwal, P. K. (2019). Retrieval practice & Bloom’s taxonomy: Do students need fact knowledge before higher order learning?. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(2), 189. https://psycnet.apa.org/manuscript/2018-26228-001.pdf Anderson, J. R., Fincham, J. M., & Douglass, S. (1997). The role of examples and rules in the acquisition of a cognitive skill. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 23(4), 932–945. Ariga, A., & Lleras, A. (2011). Brief and rare mental “breaks” keep you focused: Deactivation and reactivation of task goals preempt vigilance decrements. Cognition, 118(3), 439–443. Baird, B., Smallwood, J., Mrazek, M. D., Kam, J. W., Franklin, M. S., & Schooler, J. W. (2012). Inspired by distraction: Mind wandering facilitates creative incubation. Psychological Science, 23(10), 1117–1122. Bennike, I. H., Wieghorst, A., & Kirk, U. (2017). Online-based mindfulness training reduces behavioral markers of mind wandering. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, 1, 172–181. Berry, D. C. (1983). Metacognitive experience and transfer of logical reasoning. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 35A, 39–49. Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 354–380. Chi, M. T., Bassok, M., Lewis, M. W., Reimann, P., & Glaser, R. (1989). Self-explanations: How students study and use examples in learning to solve problems. Cognitive Science, 13(2), 145–182. Chi, M. T., De Leeuw, N., Chiu, M. H., & Lavancher, C. (1994). Eliciting self-explanations improves understanding. Cognitive Science, 18(3), 439–477. Craig, M., Dewar, M., Della Sala, S., & Wolbers, T. (2015). Rest boosts the long-term retention of spatial associative and temporal order information. Hippocampus, 25(9), 1017–1027. Creswell, J. D. (2017). Mindfulness interventions. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 491–516. Dewar, M., Alber, J., Butler, C., Cowan, N., & Della Sala, S. (2012). Brief wakeful resting boosts new memories over the long term. Psychological Science, 23(9), 955–960. Diekelmann, S., & Born, J. (2010). The memory function of sleep. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 114–126. Dudai, Y. (2004). The neurobiology of consolidations, or, how stable is the engram? Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 51–86. Ebbinghaus, H. (1913). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. (H. A. Ruger & C. E. Bussenius, Trans.). New York: Teachers College, Columbia University. (Original work published 1885) Hattie, J., & Donoghue, G. M. (2016). Learning strategies: A synthesis and conceptual model. Science of Learning, 1(1), 16013. Jensen, J. L., McDaniel, M. A., Woodard, S. M., & Kummer, T. A. (2014). Teaching to the test… or testing to teach: Exams requiring higher order thinking skills encourage greater conceptual understanding. Educational Psychology Review, 26, 307-329. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10648-013-9248-9 Kapur, M. (2008). Productive failure. Cognition and Instruction, 26(3), 379–424. Kapur, M. (2012). Productive failure in learning the concept of variance. Instructional Science, 40, 651–672. Karpicke, J. D. (2012). Retrieval-based learning: Active retrieval promotes meaningful learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(3), 157–163. Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger, H. L. (2008). The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science, 319(5865), 966–968. Kornell, N., & Bjork, R. A. (2008). Learning concepts and categories: Is spacing the "enemy of induction"? Psychological Science, 19(6), 585–592. Kühnel, J., & Sonnentag, S. (2011). How long do you benefit from vacation? A closer look at the fade-out of vacation effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(1), 125–143. Leitner, S. (1972). So lernt man lernen. Freiburg: Herder. McDaniel, M. A., & Masson, M. E. J. (1985). Alteration of memory representations: Implications for short-term and long-term memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 11(2), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.11.2.371 McGaugh, J. L. (2000). Memory—a century of consolidation. Science, 287(5451), 248–251. Mednick, S. C., et al. (2011). An opportunistic theory of consolidation. Nature Neuroscience, 14(2), 217–219. Monsell, S. (2003). Task switching. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(3), 134–140. Mrazek, M. D., et al. (2013). Mindfulness training improves working memory capacity and GRE performance while reducing mind wandering. Psychological Science, 24(5), 776–781. Paivio, A. (1991). Dual coding theory: Retrospect and current status. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 45(3), 255–287. Pyc, M. A., & Rawson, K. A. (2010). Why testing improves memory: Mediator effectiveness hypothesis. Science, 330(6002), 335. Renkl, A. (1997). Learning from worked-out examples: A study on individual differences. Cognitive Science, 21(1), 1–29. Renkl, A. (2002). Learning from worked-out examples: Instructional explanations supplement self-explanations. Learning and Instruction, 12(5), 529–556. Renkl, A. (2005). The worked-out example effect: When and why it works. In P. A. Alexander & P. H. Winne (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 529–550). Roediger, H. L., & Butler, A. C. (2011). The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(1), 20–27. Rohrer, D. (2012). Interleaving helps students distinguish among similar concepts. Educational Psychology Review, 24(3), 355–367. Schwartz, D. L., & Martin, T. (2004). Inventing to prepare for future learning: The hidden efficiency of encouraging original student production in statistics instruction. Cognition and Instruction, 22(2), 129–184. Storm, B. C., & Levy, B. J. (2012). Retrieval-induced forgetting inhibits subsequent retrieval of related items. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141(2), 355. Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285. VanLehn, K. (1999). Rule learning events in the acquisition of a complex skill: An evaluation of Cascade. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 8(1), 71–125. Wagner, U., Gais, S., Haider, H., Verleger, R., & Born, J. (2004). Sleep inspires insight. Nature, 427(6972), 352–355. Zijlstra, F. R., Cropley, M., & Rydstedt, L. W. (2014). From recovery to regulation: The role of off-job activities in the recovery process. Stress and Health, 30(2), 91–102. Chi, M. T. H., de Leeuw, N., Chiu, M.-H., & LaVancher, C. (1994). Eliciting self-explanations improves understanding. Cognitive Science, 18(3), 439–477. Dewar, M. T., Alber, J., Cowan, N., & Della Sala, S. (2012). Brief wakeful resting boosts new memories over the long term. Psychological Science, 23(9), 955–960. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612441220 Karpicke, J. D. (2012). Retrieval-based learning: Active retrieval promotes meaningful learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(3), 157–163. Rawson, K. A., & Dunlosky, J. (2011). Optimizing schedules of retrieval practice for durable and efficient learning: How much is enough? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 140(3), 283–302. Renkl, A. (1997). Learning from worked-out examples: A study on individual differences. Cognitive Science, 21(1), 1–29. Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285. VanLehn, K. (1999). Rule learning events in the acquisition of a complex skill: An evaluation of cascade. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 8(1), 71–125.